Why designing for users who don't know they have a problem matters

How to design for problem-unaware users

"It seems intimidating at first, but you get used to it," a user once told me as she went through a dozen workarounds to complete a specific task.

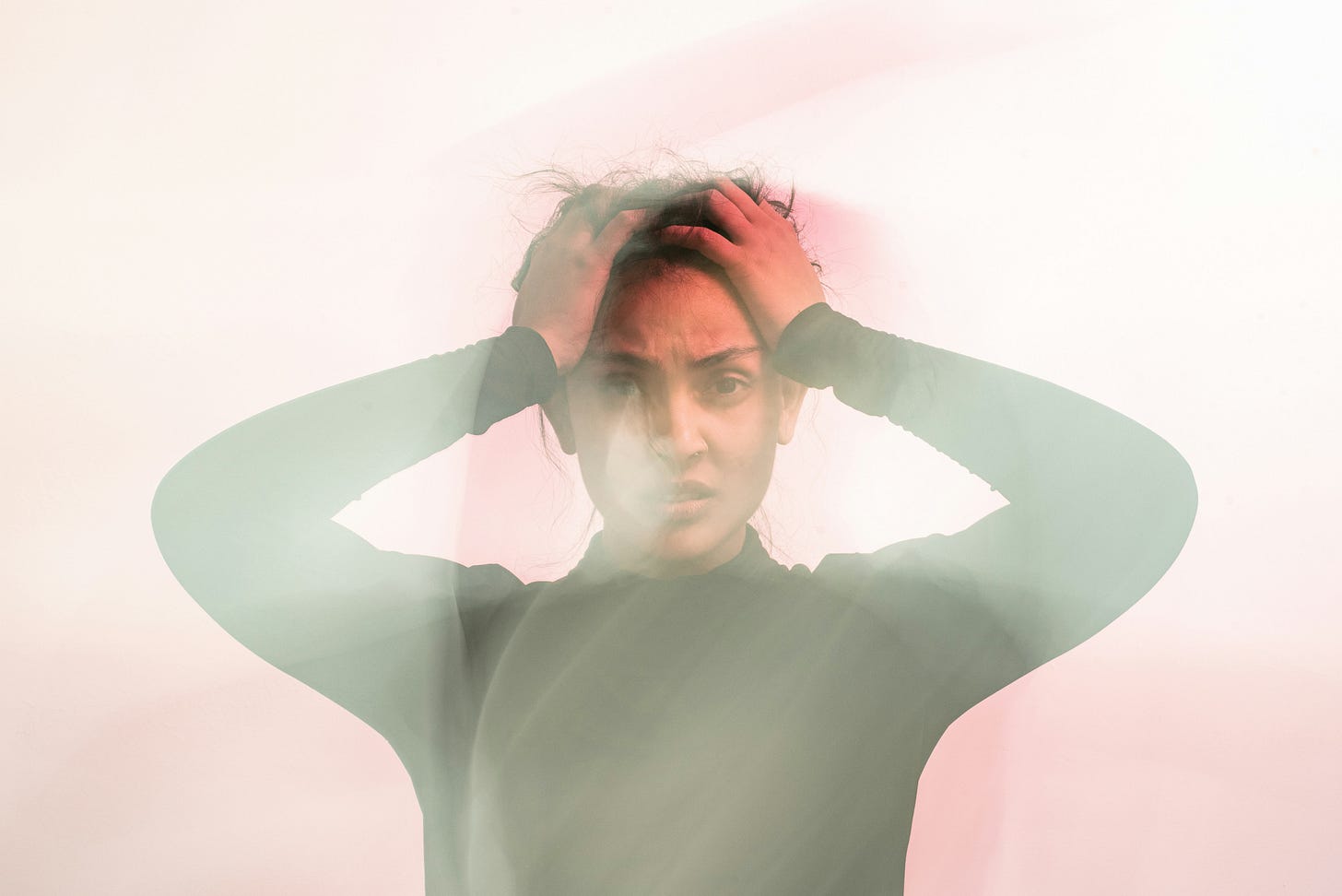

You may have heard similar things when talking with users. Users who complete tasks in seemingly broken and complicated ways. They're often, for some strange reason, resistant to change.

You've been puzzled when they say, "That new design sounds complicated. What I'm doing works fine." If that's the case, you're facing the challenge of designing for problem-unaware audiences.

The good news is that if you can address these issues, you can tackle some of your organization's biggest challenges.

Problem unaware audiences, and why they're so tricky

Problem unawareness is a concept from Eugene Schwartz's "Breakthrough Advertising" book.

Schwartz outlined five stages of customer awareness:

Problem Unaware: Don't know they have a problem

Problem Aware: Know they have a problem, but don't know solutions exist

Solution Aware: Know solutions exist, but don't know about your specific product

Product Aware: Know about your product, but aren't convinced it's right for them

Most Aware: Ready to buy, need the right offer

While UX has similar frameworks, like Jobs-To-Be-Done, they often don't cover the problem-unawareness stage.

Why? Because if users aren't aware they have a problem, they won't articulate it as a user need.

To give an example, we can talk about e-mail management.

David, the problem-aware user:

Recognizes e-mail management as a major bottleneck

Actively researches productivity methods and looks for email tools

When asked about his email workflow, David says, "I need a better system for prioritizing and tracking follow-ups."

He requests features like "automated sorting by sender importance" or "snooze functionality for follow-ups."

He understands that his current approach costs him time and seeks solutions.

Sarah, the problem-unaware user:

Manually sorts emails to folders,

Has to constantly say "Sorry, I missed your e-mail or double-books meetings,

Says "Emails just part of the job" and might request features like bigger folders or more flag color options

Doesn't realize her email management is a significant productivity drain

She views her struggles as personal failings rather than systemic problems.

You might have encountered "Sarahs" in your user testing, who say things like:

"I'm sure your product is great, I'm just terrible at technology."

"I'm sorry I'm so slow."

"I guess this might make sense to other people."

etc.

But you might not realize how big of a deal this can be. Designers often have to design for problem-unaware audiences in scenarios like onboarding.

Users might have created an account to get 10% off an order, and they're otherwise unaware of deeper problems your product could solve.

If you can't address this problem, those users will likely abandon onboarding or never use the advanced features you've designed, meaning there will be little difference between your sophisticated solution and simpler alternatives.

If that's the case? It can be hard to justify the value of design.

So, how do you design for problem-unaware audiences?

Start by surfacing the problem with language

There's a reason they say, "The first step is admitting you have a problem."

For problem-unaware users, unless you can spell out where other problems exist, they won't be able to see the issues.

One of the easiest ways to do this is to focus on behavioral triggers instead of features. What does that mean?

Tie features to real-life situations:

Instead of saying "Here's how to create a tag", talk about real needs like "Have you ever wanted to filter your files quickly?"

You can naturally raise awareness of certain features by discussing scenarios or questions they might have considered during their day.

Implement nudges around relevant user behavior:

You can also gently add 'nudges' to user behavior when the user showcases specific behavior patterns.

For example, if the user clicks the "Create a follow-up email " button three times in a row, you can show advanced automation options and say, "You've sent three follow-up emails in a week. Here's how to automate that."

Rather than overwhelming users with too many features at the start, tie it to behavior that suggests that you're reaching the limitations of basic patterns.

Use social proof strategically:

Social proof is often a great way to introduce the benefits of using specific features. It can also nudge users towards using them by mentioning their competitors.

A simple statement like "Marketing teams like yours typically save 5 hours/week using this workflow " not only showcases the efficiency of specific processes but also implies that your competitors are working more efficiently than you.

Create before-and-after opportunities:

One of the most critical questions you must address is simple: What's in it for me?

After all, what they do right now, in their minds, is "good enough", even if it is incredibly unproductive in reality. They'll have to go through the process of learning something new, which means additional effort.

To get them to not only see the problem, but act on it, you need to surface the 'pain point' comparison through things like:

Time wasted

Missed opportunities

Additional work stress

Inefficiencies and workload

etc.

Problem-unaware users are the biggest group of potential users

Problem-unaware users often represent the largest group of potential users of your product.

As a result, a good UX that gets these users onboard is tackling one of businesses' most significant problems: growth.

The UX discipline has evolved beyond optimizing poor existing user journeys: today's most successful products get people to realize they have a problem.

From Uber showing people they don't need to own cars in cities to Notion helping teams realize they could replace five different tools with one, these products shine when designers bridge the awareness gap.

In uncertain times, this is one of the most certain ways for designers to showcase their value. But to do that, you must first learn to design for problem-unaware audiences.

So if you encounter these users in your product, take a moment to understand their point of view (and what motivates them). They can lead to a wealth of untapped insights.

Have a problem-unaware audience problem? I’d love to know more. Book a call with me to tell me about your situation.

Kai Wong is a Senior Product Designer and Data and Design newsletter Author. He teaches a course, Data Informed Design: How to Show The Strategic Impact of Design Work, which helps designers communicate their value and get buy-in for ideas.