Photo by Linus Sandvide on Unsplash

The next thing that we need to understand before moving forward is another fundamental question: What makes a good visualization?

That’s a question I had to ask myself when my mentor heavily critiqued one of my early visualizations. And it was an answer that I found when reading Alberto Cairo’s The Functional Art: An introduction to information graphics and visualization.

According to him,

“A good graphic has two basic goals: It presents information and then allows users to explore that information.”

That extra step, allowing exploring the information, is crucial to promote user understanding.

And to understand this viewpoint, let’s revisit the Information-Knowledge gap.

Information-knowledge gap

One of the problems with the data pyramid, like I talked about, was crossing the threshold from something being structured information to the user knowledge. To do this requires a good organization of information, sure, but it requires something else: it requires an understanding of how your user understands or finds patterns in the data.

It may seem impossible to generalize a wide range of audiences into their information needs or expectations. After all, at this stage of the process, we might not have a clear idea of who our users are.

But surprisingly, it’s easy to understand at least how users seek out information.

They do it by following Shneiderman’s mantra.

Ben Shneiderman’s information-seeking mantra

Dr. Ben Shneiderman is a professor at the University of Maryland focusing on both Human-Centered Design and Information Visualization. This experience allowed him to develop a mantra that helps create compelling visualizations: Overview first, Zoom and Filter, then Details-on-demand.

What does he mean by this? Well, let’s take his steps with an example chart.

Overview: Scanning for a story

Users will first scan over your document to try and glean a basic story out of it.

At this point, their attention is drawn to the visual aspects such as charts while not paying attention to any of the minor details. As a result, a significant amount of time should be spent on polishing and fine-tuning the overview in whatever form it takes. If the information that is going to entice or inform users is hidden in the details, they may not even get to that point before looking elsewhere.

Given that this is how the user is first encountering your information, you want to show them that this visualization may have what they’re looking for.

For this part, you should avoid presenting too much data: instead, you can use things such as charts, visualizations, or maps to reinforce the story and reduce data clutter.

Once you’ve shown them that this visualization likely has the information they need, then comes the next step.

Zoom and Filter:

At this point, users will want to start to focus on specific sections in greater detail. This is where concepts like gridlines, grouping, and Gestalt principles play a role: by making the information visually grouped together, we make sure that the user zooms into all the relevant information in one place.

If the medium is interactive (like dashboards), then this is where things like panning, scrolling, zooming, and using filters can come into play. If not, you want to make sure that a specific section contains all relevant information so they don’t have to scan the entire document for other bits.

There’s one other bit that you will need to keep in mind, but I’ll discuss that below.

Details-on-Demand:

After this comes the bulk of the information. At this point, the user has narrowed down past the overview, chosen a specific area of interest, but at this point, perhaps they haven’t gotten the details that they’re looking for. However, what they’ve seen so far has shown them information that is either relevant to them or has caught their attention to explore even further.

At this point, then the user is willing to deal with a significant amount of information. But through proper grouping, it’s already been filtered to their specific area of interest, which means that the information will not overwhelm them.

This is very easy to do with interactive mediums, but for non-interactive mediums, at the very least, you should be prepared to show where this data comes from.

What if you don’t have enough space?

Users may seek this information in this manner, but that doesn’t always mean that you have space to include everything. By understanding how people search for information, you can add one extra thing to your infographic: a hook.

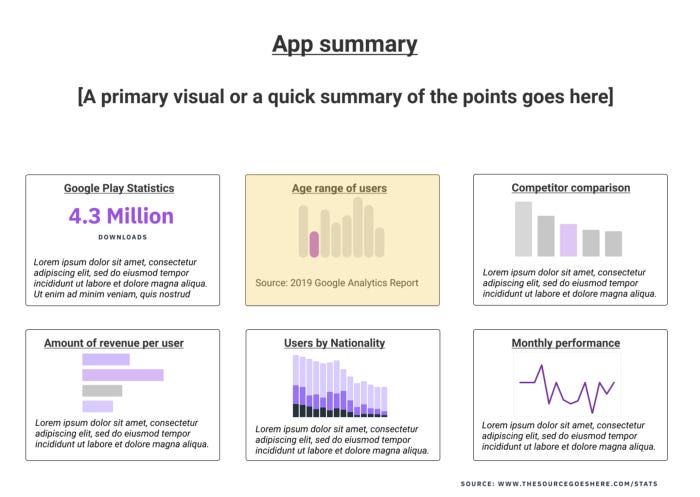

A good graphic entices the user to explore the information, which can often stretch beyond the visualization you’re presenting. So if you don’t have enough space to include everything about the Age range of users, you can point them in the direction to learn more by including sources, having additional slides (in a presentation), or providing other references.

By structuring the information in this way, you allow the user to quickly seek out the information they want, even if they have to explore other sources.

But creating a good hook requires learning one more thing about the data: it requires figuring out your message.

How messages differ from stories

I’ve talked a lot about stories and how they’re one of the critical ways of planning out the more significant aspects of your presentation. However, just as it’s vital to figure out the more significant parts of your story, you need to figure out the key points you’re trying to deliver.

That’s where messages come into play. While stories are about the organization of information, the message is the hook that gets your readers engaged in this story. For journalists working in print media, the message is one of the most important things to think about: if their reader doesn’t engage with the message, then it’s likely they won’t bother reading the rest of the story.

Working with presentation slides, dashboards, or other visualizations, we have a little more leeway: people aren’t likely to leave the room or stop paying attention immediately if one visualization message isn’t engaging.

But that doesn’t mean that you can completely ignore the message. After all, you’re still asking your audience for a lot: you’re not only trying get them to understand the data, but do things like approve specific recommendations or schedule new discussions. So engaging them with a relevant message is key.

So how should you think about your message? Ask yourself these questions:

What’s new about this data?

What is it that these people haven’t heard about? It’s very likely that your audience has some familiarity with at least some of this data. Maybe they were working on the previous step of the project with you, or perhaps they have work experience with some of this process. If this is the case, what updates, new problems, or other things should they be paying attention to?

What’s the visual hook?

Journalists tend to like having a large central image for print media and infographics. It not only immediately draws the audience’s attention with their visual system, but a large image can usually be supplemented with additional data to provide contextual clues. For example, if you were to have a human anatomy dummy as your central image, then a text box pointing to the eyes is likely going to be saying something about eyes or vision.

In presentations, data visualizations like charts are probably going to be the focus, but what is the hook that you want people to pay attention to and focus on immediately? We’ll talk about some of that in the next section, but there’s one other aspect we need to think about.

How to support information-seeking behavior?

We’ve learned about the typical way that users tend to seek information. Where should we place the visual hook so that users find and engage with it during the overview process? In the next section, we’ll also be thinking about what we’ve learned with information-seeking behavior and applying it when thinking about a piece’s visuals.

So let’s use the example that we talked about before, how the current application workflow is not working for our user group of young mothers and children. Let’s say that you’ve gathered as much data as possible, including interviewing customers and looking at analytics data. From there, you’ve discovered that because our customers keep timing out of the checkout process. As a result, you’ve found that it’s impacting your metrics a bit, particularly the abandonment rate.

What is a hook that might interest your audience in looking further? We might consider something like, “We have a high abandonment rate, and it’s largely because of one factor.”

Saying something like that gets your user’s attention in a way that merely presents the same information doesn’t: that type of situation can be uncommon in the business world, so they’re inviting people to learn more about this.

That’s where exploration can come into play.

Exploring to learn

Sometimes, there’s too much information to condense into a single visualization. But there’s no use in trying to cram everything in regardless.

Instead, we should support the user’s information-seeking behavior to not only allow for clear exploration of the visualization but keep exploring for more information beyond what’s available.

A good visualization can serve as a summary, but it’s almost certain that some audience members will want more details than provided.

Now that we’ve made that distinction let’s go ahead with the following section: Thinking about the best graphic form.