Visual Design is important, but it’s not the only thing that matters

How to present your work when it isn’t visually stunning

“I’m not sure what to do. There seems to be a heavy emphasis on Visual Design,” a designer complained, reminding me of where I struggled years ago.

There’s no getting around it: many organizations nowadays prioritize visuals. Applying to specific jobs often requires showing high-quality and beautifully designed visuals in your portfolio.

But that emphasis leaves some of us, myself included, wondering how to present our work.

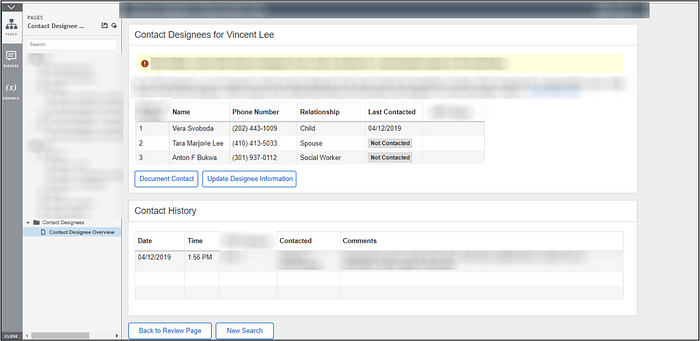

My first projects weren’t visually interesting. My design work revolved around fixing form fields and upgrading 30-year-old visual interfaces.

If you’re suffering from the same issues I was, you must first understand why businesses focus so much on visuals.

Aesthetics, usability, and tangible outputs around design

After working as a UX team of one for a lot of my career, I’ve found that a few things drive demand for high-quality visuals.

First and foremost, beautiful interfaces are perceived as more usable (Aesthetic-Usability Effect). When an interface looks nice, not only do people think it’s more usable, but more people will tolerate UI problems when something looks nice.

However, this effect has its limits. After all, most businesses don’t want to create art pieces that don’t do anything. They want high-quality visuals that drive action, like getting users to create an account or clicking to learn more.

“Design is NOT art. Design has to show value.”-Donald Judd

So, while high-quality visuals are appreciated for their appearance, businesses often like them because they are tangible output.

Not everyone knows much about design, but if you show them a “before” and “after” visual of your re-design, they can immediately tell what the designers did.

However, this approach has a significant flaw: it leans almost entirely on visual distinction. Imagine if the big problem you found with users was Information Architecture: they didn’t understand how to work your menus and were getting lost.

If you changed the menu labels, which fixed the usability problems, it would look like you did 20 minutes of work from a visual perspective.

So whether your visuals aren’t that fancy or the before-and-after images aren’t going to look great, designers can employ another strategy to show their skills: lean into business impact.

Don’t trip up on the first step: Spell out the Problem clearly

Designers often trip up at the first sentence of their portfolio because they immediately jump into the details before setting up a problem. Imagine a conversation went like this:

You: “Hi.”

Interviewer: “Hi, how are you…”

You: “So my latest project was about fixing a Payer-Provider Portal with the CMS side, which involved a lot of talking with….

(Interviewer: I just sat down. Is that really how they’re starting the conversation?)

Here’s the thing: if you want to show that you’re a great designer who knows how to solve problems, you must first define the problem statement well enough that your audience understands it.

You might have a problem statement, but there’s often a few things wrong with it:

You don’t establish any context (“Company X creates point-of-care clinical pathways for neonatal care…”)

You don’t spell out a problem (“We were asked to design a new checkout process.”)

You give too much context (“Company Y works in the payer-provider space. Here are eight slides explaining CMS, payers, providers, and how they work together…”)

You use too much jargon (“Company Z does ICMP/SNMP monitoring, along with Syslog, Azure, and WSMan discovery.”)

etc

Remember that people often encounter your portfolio for the first time without context about who you are or what you’ve done. If they don’t understand what problem you’re aiming to solve, they won’t understand the tangible output you created.

One of the simplest ways to do this is through a template and a Google search. It goes like this:

My project was about [Market Research about the area you’re working in]

This field/project has problems with [Problem X, Y, Z]

Here’s what I needed to design as a result

You have to Google the first sentence to link your problem to business impact easily. Ideally, you’d have the metrics from your team, but a simple cursory search can give you much of the impact you need.

The second sentence is about defining the problem in broad terms. What were the problems users had with the project that caused you to get involved in the first place?

Then, you can transition into what you need to design to complete the problem statement.

Here’s how that might work out.

My project was about [Medicare/Medicaid for Disabled Seniors, a highly competitive $1.6 Billion Industry]

This field has problems with [Designing Accessible Interfaces, Getting Seniors to use websites, and simplifying complex insurance terms]

Therefore, I needed to design [a usable interface to help disabled seniors find medical providers covered by Medicare]

When you have that, you’ve done half the battle in ensuring that people understand what you’re doing with this project.

From there, you can move on to a desired outcome.

Show outcomes, not design solutions

After you spend time setting up an understandable problem, you set up the outcome.

I say outcome because many designers often stop showing the “final design solution,” which doesn’t show they’ve solved a problem. That would be like defining the problem in words and posting an “After” screenshot as a solution.

So, your outcome should ideally be in one of these forms:

Business outcomes/Metrics

“Predictive” User Behavior

Annotated design solution

Ideally, you would have some metrics from the business, as this is the quickest and most straightforward way to show great outcomes.

For example, pointing to a 20% reduction in people who abandoned the “Find a provider” process is a tangible output that businesses understand almost immediately.

However, you don’t always have that data. As a result, you might lean into ‘predictive’ user behavior. What signals did you see during user feedback sessions that led you to believe you solved a user’s problem?

Did they, for example:

Breeze through finding a provider, not realizing it used to be a problem?

Talk about how the process is so much better now?

Explain concepts around the process that people used to get stuck on?

etc.

Lastly, you can use a screenshot of the design solution, but you would need to annotate it with the changes made (and the outcomes) to point to where you made a tangible difference.

Besides high-quality visuals, these are ways to show that you’ve solved a user’s problem.

Visual design isn’t the only thing that matters.

High-quality visuals (i.e. non-blurry images) are a requirement for portfolios.

But that doesn’t mean that work that leans heavily into Visual Design wins over everything else.

Whether you’re designing boring stuff like form fields, are only okay at Visual Design, or have projects that aren’t easy to emphasize visuals on, there is another way to showcase the value of your work: problems and solutions.

It often matters more that you re-designed that annoying form field that users hate rather than creating a beautiful homepage.

But if you’re not sure of how to present work that looks mundane, focus on defining the problem and solution. That can give interviewers what they’re looking to find: the tangible value of hiring you as a Designer.

Kai Wong is a Senior Product Designer and Creator of the Data and Design newsletter. His course, Data-Informed Design, shows you how to work more effectively and complete design projects faster without sacrificing quality.