Version control is a skill UX can learn to make their lives easier

Use Components, Variants, and Pages to provide different design versions your team members need

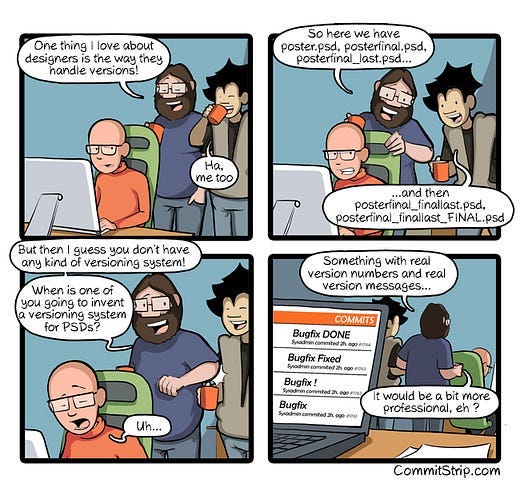

Version control for your design prototypes is one of those things you never think about until you desperately need it.

Version control is so essential that many Engineers will devote time and effort to build or buy these systems because it tracks changes across systems and programs.

It might seem like overkill for designing, but when you need:

A scaled-back version for Engineering,

A no-limits version for Product teams or Executives

One for each user test, and

Your workspace version

You’ll be glad that design software has version control tools.

But to understand these versions, let’s first talk about version control.

UX version control: Components, Variants, and Pages

To understand what Version control is, we first must talk about what Engineers do because they use it constantly.

Version control is a concept that Engineering uses, at its core, to track changes. However, there are a lot of working parts when it comes to the product's codebase, and you want to ensure that you know who is working on what to be able to track progress.

If something goes wrong with the current version, they can revert to the previous version to get things working or break out a separate version to try a different solution.

UX Design sometimes needs this approach, especially when your sprints are designed around components. Luckily, version controls are built into a lot of Design software in the form of Components, Variants, and Pages.

To explain why let’s talk about two different versions, you might already be maintaining: your design workspace and a user-testing version.

The UX Design workspace and a scaled-down version for testing

You don’t always user test with the same version where you work.

Usually, you want to limit the design you’re user testing to whatever tasks you want to gather feedback on and a few design alternatives. In addition, while you may be working on different things in the background, you may not want to make that accessible to the general public.

Lastly, user-testing versions are usually frozen in stone. For example, you don’t want to show your participants five different designs, and you might want to reference that exact design later (especially if you asked about design alternatives).

This is where you can use the versioning tools to help. Rather than recreating the design entirely, we can use our version system:

Components, to make templates of design elements

Variants, to show different designs of components, and

Pages, to have entirely separate reference points for different versions

I’m using Figma terminology here, but most software uses similar terms(in Axure, its components, states, and pages).

Why go through all this trouble of version control? The answer lies at the end of the user testing process: incorporating feedback into the next Design.

To understand this, we need to talk about Master Components.

Using Master Components in your Design workspace for easy iteration

Master components, simply put, are how you can quickly change several components at once. Using these can allow you to avoid the headache of having to change individual components in your design.

This becomes especially important if user testing provides feedback that suggests changing several design elements. If you have two separate files (as you probably should), having them built with the same Master Component allows you to change the designs quickly.

If you didn’t use this versioning tool, you might be able to get away with re-doing it in your Design workspace. However, that tool can help you iterate and quickly make relevant changes.

This time-saving becomes even more pronounced when you need to provide versions to other team members, like Engineering.

Engineering wants a prototype to act as a source of truth

My lead Engineer once used this phrase, which makes sense for this type of version. In essence, what Engineering wants is one place to turn to for referencing what they need to build.

However, problems arise when you realize that Design ideally works 2–3 sprints ahead of Engineering. Engineering wants to turn to the prototype for what they build in this sprint (and maybe the next), but they don’t want to be surprised each time they open the prototype.

If it was the same version UX is working on, it’s not only constantly changing, but it might include work outside the scope of what they plan to do for a sprint. This becomes especially problematic if work sprints are broken up by component instead of a page.

To explain this, let’s look at a simple table component.

UX Designers might look at this table, with all of the existing columns, and think it’s finished. After all, these are the columns of information we want to show the user.

However, a Software Engineer might look at this and panic. Why? It may be that columns C, D, and F are not yet hooked up in the backend. When they see the prototype, they might think, “wait, do I have spend the time to hook up these components in the back-end (while building this table)?”

I’ve seen engineering teams develop less-than-stellar solutions for this (i.e., print out the prototype and X out the sections they weren’t working on), but that might throw things like alignment and spacing out of wack.

Instead, it’s much easier for UX Designers to create another version for them.

Creating a scaled-down version for Engineers:

The first step of this process is creating a duplicate Page for Engineers, which is the first thing they see when loading up your Figma file. I can’t tell you how often I’ve heard complaints from Engineers when it wasn’t structured this way.

From here, you can take the Components you built out in your Design workspace and create Variants with them.

This way, engineering can see that scaled-down design without recreating another component from scratch. This allows Engineering to use this version as the visual reference for what they should build for this sprint without interpreting what you build.

But this isn’t the only version you might need.

The product team wants to keep track of the big picture

Lastly, there may be another version that you’re asked to create to keep track of the big picture. The most common situation I’ve seen for this tends to be one of two situations:

Engineering wants to scale back/cut features for the time being, but Product wants to save them somewhere

Product wants a Vision of the Future, nine months later Design to think about

These versions are much more forward-thinking, ensuring that things we cut in the short term are not lost in the longer term.

These should not be exclusive features built out just sitting here: this version will most likely be incomplete, and that’s fine. However, depending on your product team, you may have to put in some work to mock up a potential vision (even if it’s not complete).

In Articulating Design Decisions, Tom Green describes this as the “no-limits vision of the future”. Sometimes, the product team (or executives) want to imagine the future with a particular feature, and you’ll be asked to mock something up.

For example, it might be that the “search bar” doesn’t just support searching by name: it can cross-reference a database to find people based on SSN, address, or other things.

However, the most common example comes from the cut features: Engineering will say, “that sounds great, but we can’t handle that right now,” and Product will reply, “Well, let’s revisit that later because we want that feature.”

In those cases, this will be the version where those ideas live. It might need to be finished and hooked up, but the general semblance of the idea will live there.

That’s one of the best things that organizing your versioning can help you with.

Versioning provides smooth transitions and tracking ‘progress.’

While maintaining these different versions of designs might be a little complex, there are many benefits to making this effort.

The first is that transitioning from UX to Engineering work becomes much more manageable. When the team can see the difference between the “Engineering sprint” version of a design and the “2 sprints later UX” design version, handing it off to Engineering with fewer questions becomes more accessible. It also gives Engineering a preview of what’s coming up, which means they’re less likely to be surprised.

The other main benefit this offers is making UX work visible and showing progress in the backlog.

I worked with many new product owners and managers, so I’ve dealt with people unfamiliar with writing user stories (and how UX can fit into the Agile backlog). Versioning helps with both of those.

Having the versions laid out shows the progress that UX is making across the design space, along with being able to reference a visual component with user stories. It also allows the Product team to zoom out and see how different user stories relate and interconnect.

Lastly, it helps UX cohesively organize their designs. I’m guilty of having too many similar-sounding names, which means keeping track of the latest version can be tricky.

So if you feel like you’re juggling several different design files for your projects, consider using the Versioning tools that your design might have. This can not only provide specialized views each of your team members needs: it can save you a lot of headaches with consistency across your designs.

Want to become a UX professional? I’ve written a free e-book explaining how to make yourself an ideal UX candidate.

Kai Wong is a Senior Product Designer and a top Design Writer on Medium. His new book, Data-informed UX Design, explains small changes you can make regarding data to improve your UX Design process.