To get interviewers to engage with your design portfolio, tell a story

How a five-minute story can help you engage with interviewers

"I'm not having much luck with interviews," a Junior Designer said as we reviewed his portfolio. "I usually don't get past talking with recruiters."

Like many others, he was following what he learned in school in a design portfolio: he laid out the overall context, the background, his design process, and more. That was what school had taught him to do, and following that had only netted him a few interviews in 6 months.

This article is about something other than the best way to layout design portfolios. Instead, I want to talk about a fundamental mistake I've seen many designers make when presenting their portfolios.

Regardless of your design portfolio structure, you must translate your projects to answer your audience's questions. Here's why.

Your design portfolio is meant to summarize, not focus on skills

The purpose of your design portfolio is to act as a conversation starter. In other words, you have a quick summary of a few main things:

What was the overall goal of this project?

What problem were you trying to solve as a designer?

How did you use design to solve that problem?

What sort of impact did you have with your design process?

The idea is to have enough for audiences to understand the basics and, if interested, ask you about it in detail. In essence, presenting a design portfolio project answers the question of "Tell me about project X." in detail.

However, recruiters (and interviewers) don't always ask that question early on. Recruiters are (mostly) external audiences who may not know everything about the design process.

As a result, they’re trying to answer one specific question: "Does this candidate show that they have experience with X skills that match the job description?"

As a result, they'll ask you questions like "Have you ever worked with Figma before?" or perhaps "What would you do if your Product Manager disagreed with your design recommendation?"

These questions aren’t about summarizing your design projects. They want to see how you’ve used specific skills or faced specific real-life situations.

As a result, the fundamental mistake I've seen many Junior Designers make is simple: they don't translate their portfolio, so they only partially answer the question. They'll reply, "Yes, I worked with Figma on this project," before summarizing their design portfolio again.

Your audience seeks a way to convey how you used these skills and their impact. One of the best and most engaging ways to do this is to use a storytelling framework called a 5-minute story.

The 5-minute story and how it's useful for designers

The idea of condensing months, if not years, of project background into something short and straightforward is impossible. But that's the thing: you don't have to. All you need to do is have enough background to start crafting a story.

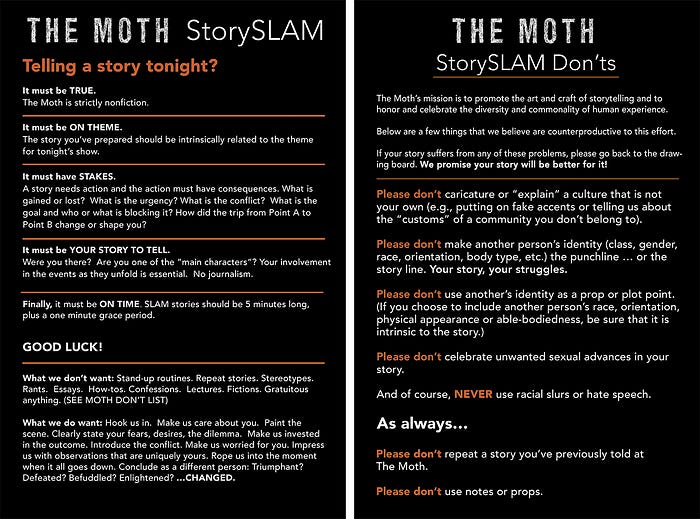

Enter the 5-minute story. In a previous article, I talked about how the Moth, a competitive storytelling competition, is where top storytellers go to tell 5-minute stories that engage audiences and move them.

I didn’t mention that it’s also a natural extension of a workshopping method called the 3-minute story, which summarizes and drives action around presentations.

Learning to tell a 5-minute story not only helps you clarify what you’d communicate to others (especially if you’re short on time): it’s a re-usable template. Once you figure out the 5-minute story framework for a particular project, you can adapt it to your interviewer's requirements.

To do that, it first starts by talking about your character.

What needed to change?: The character and the problem

At a fundamental level, design stories are stories about change. We're asked to design or redesign something because the business decided the current state of something is unacceptable.

If you're redesigning something, you got put on that project because management deemed the current design and metrics unacceptable enough to invest time, effort, and resources into fixing things.

Likewise, if you're designing something new, the business deemed the company strategy/market fit/etc. unacceptable and in need of a change.

You might not know the exact business reasons a project started, but you probably know something else: what are the current problems, according to users?

This is where you can often start your design portfolio story. If users are currently facing issues with the current design, what are these issues?

The other thing to mention is that you are not the main character; users are. You're not trying to convince your interviewer that you understand yourself. You're trying to convince them that you've understood your users in the past so that you will also understand their current users.

For example, imagine one of your projects was a redesign of a medical homepage, and this is where you used FigJam, which is the question the recruiter asked you about.

You might want to start your story in the following manner: "I used Figjam extensively when I was working on Project X. Users were having trouble finding the relevant medical information they needed on our homepage, which was troubling because this was critical information they needed for their treatment. As a result, both user compliance and satisfaction were low."

This is a great starting point for the story because it tells us a couple of things:

FigJam is somehow essential and helpful in Project X

Users were having critical issues that needed to change

(Recommended) Here are some UX metrics or things that were affected

However, notice how short this introduction is. I've discussed it before, but you don't need to introduce all the potentially relevant context here. You only need to introduce the main character (the user) and their problem.

When you do this, you give enough starting points for your audience to follow without getting lost. Even if they don't understand some of the terminology, they can follow along if you can quickly summarize the user's problem (and possibly relate it to standard metrics they're familiar with).

Next comes the moment of transformation.

The moment of transformation or how things got better (with you)

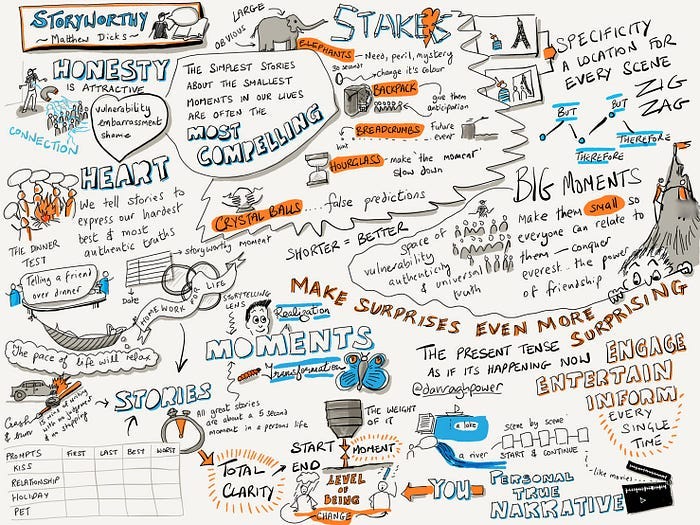

While I first heard of the 5-second moment from Storyworthy by Matthew Dicks (Link), other authors, like Kindra Hall's "Stories that Stick," have also explored a similar concept.

If a story is about change, there's a moment in the story where this change must start to occur. Change is often gradual, but there's often a moment in your project when something shifts with your users.

This is where you, the Designer, come into play. What did you do, and how did it impact the main character's (i.e., the user's) life?

Was this moment during the first user test when users were suddenly excited about your changes? Was it when you talked to a subject matter expert, and they breathed a sigh of relief because it seemed like you finally were tackling a problem that had frustrated him to no end?

You want to show these moments more than design artifacts or sketches because they showcase something straightforward: this is how we know we are on the right track.

Tying it back to the skills-based question, we might talk about how we used Figjam throughout the process and when you started to make a lot of progress.

For example, "I used FigJam during this process to help us brainstorm a better navigation menu, because many of the user's issues came from confusion around navigating to the right page. By creating Card-sorting diagrams in FigJam and testing them with users, I could see what worked for users and what didn't. I knew I was on the right track, with FigJam, when all of my users unanimously agreed on a menu layout."

This is also where, if you have them on hand, including specific user details, such as user quotes or sighs of relief, are at their most potent. These details help to establish it's not just us saying that this was useful; the users themselves showed that.

Once you do that, you can move on to the last section: talking about the impact.

The impact is the secret ingredient many designers miss

The last, and often most important, aspect of this story is the impact of your actions. This is where even experienced Designers fumble, and it's easy to understand why.

I get it. You don't see the impact if you're working in specific environments, like design agencies. By need to finish the project, you're already on another one, without getting a chance to see what happened to the previous one.

But nowadays, more is needed. When budgets are tight, businesses want to ask the ugly, age-old question: what is the return on investment (ROI) of UX? Pointing to some outcomes, measures, or impacts will help you here.

If you're stuck like some designers I've seen or have yet to learn about the impact because development took months to build, there are a couple of ways around this.

First and foremost, if the sites are publicly available, navigate to them and show the before and after. The idea is that, in some cases, the changes are so drastic that a simple visual representation of what you did and how it changed is enough.

This is the approach that I sometimes use in my federal work, where the site goes from looking like it came out of the 1990s to a more modern approach.

However, if the visuals don't immediately communicate your impact, consider other sources. Ideally, you would have access to analytics or talk with someone who might be able to show you the quantitative impact your design had on the users.

However, you can at least talk about the qualitative impact if you don't have access to that.

For example, can you talk about the first user tests you did and compare them to the last? Did the emotions involve a change from extreme frustration to more acceptance and levelheadedness?

In addition, if you're talking to a recruiter and answering that question, what did you learn from that experience with a specific tool or skill?

For example, "We significantly re-tooled the menu navigation and simplified the homepage to guide users towards one clear action: choosing a medical department to get your treatment information. As a result, the amount of support tickets we got (and complaints) requesting information available on our website decreased significantly."

The five-minute story I've spelled out throughout this article may not be perfect. We, as Designers, know the importance of iteration. However, answering questions with this storytelling context may help us ensure we're not boring our interviewer with context: you're telling an engaging story.

Storytelling helps engage interviewers with your design portfolio

Can I claim that storytelling is the ultimate design portfolio strategy? Probably not.

Some interviewers may want the traditional design process structure outlined from step to step. In addition, I work in more complex fields: what people are looking for in things like e-commerce UX positions may be completely different.

However, I know the power of storytelling: I've seen adamantly opposed stakeholders be persuaded through the power of a narrative, and I explained otherwise incomprehensible projects, such as designing an interface for laparoscopic surgery, quickly to recruiters.

Telling a story around your design portfolio is not rocket science. All it requires is an understanding of a couple of things:

Who’s your user, and what’s their problem?

When did you start to see a change occur?

What was the impact of that change?

When you can answer those questions, you can create a 5-minute story to tackle any skills-based question a recruiter may throw. Moreover, these stories can engage people with the UX process and show how you can improve their organization.

So, if you need help or are trying to explain your design portfolio in a relevant and timely manner to recruiters, interviewers, and more, try reframing it as a story. When you do that, you may be surprised at how engaged they truly may become with your work.

I’m creating a Maven course on Data Storytelling for Designers! If you’re interested in learning (or would like to provide feedback), consider filling out this survey.

Kai Wong is a Senior Product Designer and Data and Design newsletter writer. His book, Data-Informed UX Design, provides 21 small changes you can make to your design process to leverage the power of data and design.