Need to persuade higher-ups to align with user needs? Use data storytelling

The 3-step plan Data Storytelling offers to help designers persuade organizations to change

Sometimes your user research, unfortunately, uncovers significant issues that need to be addressed.

Uncovering these issues is okay; in fact, it is critical to uncover these findings. However, doing so may often force you to challenge long-standing beliefs in the organization.

Whether it's users not following the organization's intended workflow or users not interested in a new feature the business is building, sometimes you have to be the one that challenges and shifts the team's understanding.

Design storytelling can help us determine the best way to create a narrative around our findings. However, to persuade and change stakeholders' minds, it's worth looking at Design Storytelling's more mature cousin, Data Storytelling, to help us out.

Data might overturn people's opinions, but storytelling will

Storytelling is one of those skills closely tied to what we do as designers in the design process. Whether generating a journey map or presenting user insights, much of it can be augmented with the power of storytelling and the narrative arc.

However, a closely related field, data storytelling, can be incredibly persuasive in changing people's minds.

The main difference between the two fields is that data storytelling asks one additional question that's useful for persuasion purposes:

How can I use my data to make my point visible and shareable?

This is especially useful for persuasion, as you're often not just targeting one person: many throughout the organization may see your ideas and presentation.

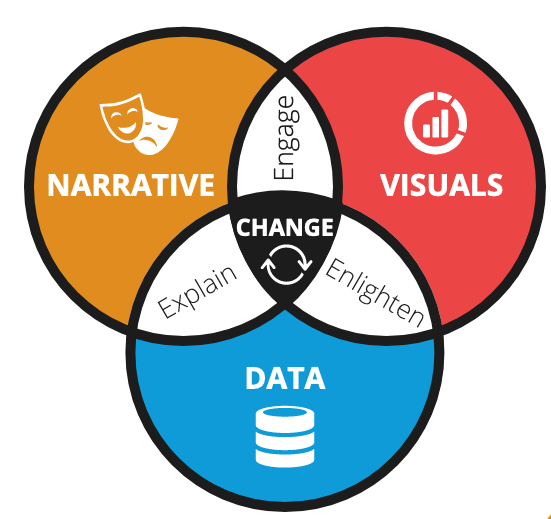

To help persuade critical members of the organization, Data Storytelling usually follows a three-step process:

Build a narrative

Create Visualizations to highlight critical insights

Support your points using data

These three factors (Data, Narrative, and Visualizations) of Data Storytelling help to persuade audiences by providing everything they need to know.

To illustrate this, let's talk about two medical professionals whose lives went very differently based on how they presented their findings: Ignaz Semmelweis and Florence Nightingale.

The Persuasive Power of data storytelling

Neither of the medical ideas that Semmelweis or Nightingale introduced would be radical by today's medical standards, but they were at the time. Semmelweis advocated for doctors to wash their hands before delivering a baby, and Florence Nightingale advocated for changing bedsheets and providing basic sanitation for soldiers.

Yet their two approaches had very different results based on how they presented their data. For insinuating that doctors were at fault, Semmelweis lost his job, was ostracized by much of the medical community, and ended up in a mental institution.

He had the approach of letting the data speak for itself: sometimes, he would scold people who wouldn't look purely at the facts.

However, Nightingale understood her target audience: she needed to persuade military generals who out-ranked her (and later the public), who had a long-held assumption that most casualties came from the front lines.

When she collected data, though, she saw that most casualties came from wartime hospitals, often 3–4x as many as from the front lines.

This allowed her to form her narrative: more soldiers died of preventable diseases during wartime due to easily preventable diseases.

Yet she likely would not have had much success without the visualization she created, the polar chart.

She recognized that many of her target audience had poor data literacy, and few knew how to read statistical tables. So she sought to convey statistics and key insights in exciting ways that attracted attention, engaged readers, and were accessible to the public.

The visualization was easy to read, easily shareable, and provided concrete data that showed something easily fixable.

As a result, her combination of data, narrative, and visualizations eventually convinced wartime and civilian hospitals to implement better sanitation policies.

While you won't have such urgent stories to tell with lives at stake, learning from Florence Nightingale's data storytelling can provide a template for challenging long-held beliefs in your organization. In addition, you don't always need to be a 'numbers' person to tell a great story.

How can we apply this thinking to our user research? By augmenting things we already do.

Storytelling with data means leveraging visualizations

Imagine you've found a critical user insight: users aren't interested in the feature release your team has been pushing for the last six months.

The current first release needs a critical feature, customization, that would drive users to purchase a subscription.

This means you need to tell your team, who's in the middle of pushing for the release, to think about delaying so you can include a critical feature. This means not only your team but upper management as well.

How might you tell this story? It starts with the narrative.

Form a narrative around your audience's tension

As I discussed last week, the first step would be forming a narrative arc around your audience's tension. Specifically, what are they worried or tense about that they're looking to you to resolve?

In our situation, we have much more tension than they might have anticipated. They were turning to you to understand minor issues they could fix based on user feedback for early release, and you're coming back with a significant missing feature.

So one idea you could do is frame it in a way they expected, up until the climax.

You expected that they would only encounter minor issues, but the main issue is you encountered a huge issue regarding user motivation and customization. After that, your narrative might conclude with two less-than-ideal potential solutions:

Ignore the missing critical feature partially: Adjust the design to have the option for customization, but then have it lead to a page that says "Coming Soon."

Build out the customization option by delaying timelines: Incorporate the feature entirely by spending extra time and resources to include the function.

After this, we move toward the Visualization aspect.

Visualize specific aspects your team should pay attention to

We’re not constantly creating bar charts when discussing visualization: the main point is to draw people's attention through visuals to engage and share your ideas.

Designers can use this by augmenting many of the UX techniques we already do to make things more shareable and accessible.

Visualize Context around Highlight Reels:

One of the most common ways to convince stubborn stakeholders is to refrain from saying anything. Instead, you compile a video highlight reel to show the users struggling through tasks with the video you recorded.

Data storytelling also helps resolve one of its most significant weaknesses: you might want to fit too many things into the reel. By forming your narrative arc first, you must consider which clips you want to include.

It can be a powerful way of communicating where users have issues, but creating a simple visualization about the context is often the extra step that helps mitigate any rationalizations your team might have.

I've heard all types of excuses, from "This particular user must be dumb" to "That's a rare occurrence we don't have to plan for," and it can help pre-emptively visualize these findings' impact. Here are some visualizations you could create:

A bar chart showing that a particular task takes twice as long as others to complete (on average)

A stacked bar chart showing how users rated a particular task low compared to others

A pie/donut chart showing that the majority of users tested ran into a particular issue

The point is to consider not just the people you're presenting to but how easily shareable something is. It does no good for you to explain to your team that this isn't just a dumb user during your presentation, only for your Project Manager to share your presentation with others (and have them assume it's a dumb user).

Consider providing the context within the presentation so that if other people want to watch the highlight reel, they know exactly what is happening here.

Visualize the journey around Quotes:

If you can't record videos of users, one of the most common techniques is to note down specific quotes, which you present to your team later on.

However, the mistake many designers make is thinking that a quote can stand by itself. Sometimes you get those rare quotes that can capture a user's frustration in a way that provides context, but more often, you get something like this:

“That isn’t too fun. I’d like for it to be able to provide me with a list of options instead of remembering what to type.”

Looking at the quote above, you need to provide some context into what 'that' is, along with 'it' and many other words.

What could be more helpful is to help visualize where they are in the workflow to help capture where they're running into issues.

This is where a simple visualization can help: the emotional arc of a journey map. Whether you've built a journey map (or haven't), this can provide additional context to where these quotes are happening quickly.

For example, if several quotes expressing user frustration are around a specific task, where exactly is this happening?

Understanding which page it occurs on is great, but understanding how far a user may be along a process may tie into other data we might have (such as Analytics which says that many users are abandoning tasks on a particular page).

Visualize your key insights

Lastly, remember that simple Data Visualizations, like summarizing key insights with bar or line charts, can be a quick way of not only ensuring that your team is engaged but also that it can be shareable.

Data Visualization often simplifies and clarifies dense and complex data in a graphical form, and part of that process is understanding what users care about.

I've seen presentations that waste their visualizations by showing demographic data or other things that might not matter, which is a shame. If you're trying to persuade people, your arguments often must reach a wide range of audiences, and they will only sometimes have the context you provide with a presentation.

Visualizing your key points can provide enough context to ensure they draw the same conclusions, even if your presentation is passed to another person.

End with design recommendations or actionable next steps

The last thing to remember, especially with persuasion, is to give clear next steps or recommendations.

I've seen great and persuasive presentations fail because the presenter provided no next step. At this point, if you're challenging the long-held beliefs of the organization, you need to provide proper guidance on what to do instead.

Remember that you're taking action for your users, meaning you must understand what you're trying to convey moving forward. While the business may not always listen to UX 100%, you want to ensure they understand precisely where you're coming from and what you should implement.

If you've ever found yourself tasked with trying to change your organization's beliefs in the face of user research, consider the impact that data and design storytelling have in persuading your team.

Using them often means the difference between ideas being accepted and implemented vs. having your organization ignore your input.

Kai Wong is a Senior Product Designer, Data-Informed Design Author, and Top Design Writer on Medium. His new free book, The Resilient UX Professional, provides real-world advice to get your first UX job and advance your UX career.