If you want to test the fundamentals of your design, take off your glasses

A quick way to make use of “people don’t read, they scan’”

Sometimes, correcting the most fundamental issues with your designs doesn’t require user testing.

I’m not advocating cutting out user research—far from it. Instead, I’m advocating double-checking your designs for basic mistakes so that you make the most of your user testing sessions.

For some of us, it’s as easy as taking off our glasses. To understand why, we must start with five words we accept as a nearly universal truth: people don’t read, they scan.

The near universality of information-seeking behavior

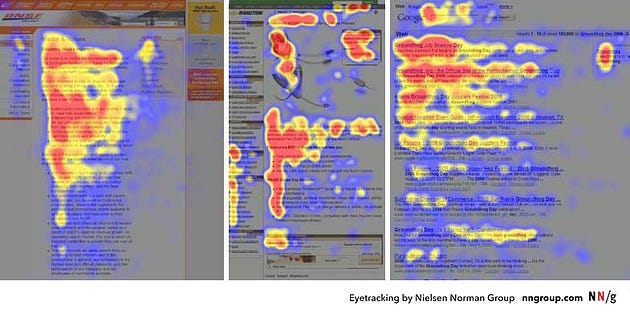

When we hear about user scanning, we often think about F-patterns (or Z-patterns) and how we can think to design a page around that.

However, these concepts aren’t always helpful in designing a page other than providing general advice (like aligning to a grid).

Instead, if we accept that most people scan websites, an idea called the Information-seeking mantra can help us understand how users navigate through your site.

The idea comes from Ben Shneiderman, an Information Visualization pioneer, who developed a three-stage process for how users seek information:

Overview (Scanning for any elements that catch your attention)

Zoom & Filter (Selecting an interesting element and zooming in)

Details on Demand (Finding additional information)

With a few caveats, this process can apply to most scenarios where users seek information through visual elements.

First, due to the focus on visual elements, this will not apply to certain demographics, such as blind users with screen readers.

Secondly, this is mainly intended for websites or applications where users actively seek information. As a result, this may not apply if you’re designing something meant for casual browsing (such as a social media site with infinite scrolling).

Lastly, this is not called the Information Understanding mantra: While most users follow this process (due to how our eyes and brains work), they may not all understand what we’re showing.

However, it’s through this process that we can do some quick tests of our design fundamentals with one simple trick:

Take off your glasses.

The Blurred Vision rule, or how to use Information-seeking in design

One of the problems with the Information Seeking mantra is that this process happens almost instantaneously.

We don’t go through a manual process of “Hey, I noticed something here in the overview. I’ll pause here for a second before zooming in.”

It might seem like you need a fancy eye tracker or MRI to break down these process stages. But I stumbled upon a really easy way to break down information-seeking and use it in your design process: Take off your glasses (or contacts).

This is what I call the Blurred Vision rule. While I initially used it to create better Data Visualizations, it’s also been instrumental in polishing my designs.

Even if you don’t have glasses (or contacts), progressive blur is not that hard to use. Figma has a tutorial about it that achieves a similar effect.

These quick extra steps allow you to double-check for basic problems before putting them in front of a user.

Here’s how to do that.

Applying the Information-seeking mantra to your design process

I’ll walk through the steps of the Information-seeking mantra while using the “Progressive Blur” feature in Figma to emphasize how I might walk through this process.

Overview: “Take off your glasses” and look for what draws your attention

Some things stand out when we add this Blur layer, mainly through color, text, and size. At this stage, the main thing to do is to take a moment and write down (or highlight) the blobs that jump out at you.

I’ve mainly selected the blobs of color that stand out, along with the big “Project Management” that’s still legible with the blur filter.

Questions to consider at this stage:

What things jump out to you as points of focus?

Are these what you want your users to focus on?

After that, we can Zoom in.

Zoom & Filter: Applying Gestalt principles (Proximity) and checking focus

Once you’ve noted the eye-catching blobs, unblur one of these focus points and examine them closer. In Figma, you’ll need to add a rectangle and “Subtract Union” to the blur layer to unblur a particular part of the design.

If you’re removing your glasses, put them back on, but hold a piece of paper up to the screen so that most of the design is hidden (except what you want to focus on).

This allows us to test a few things. First, we can test whether or not our focus was drawn to the right thing. For example, if our attention was drawn due to the blue square, and it turns out it was just an extraneous icon, we might consider de-emphasizing it so that it doesn’t draw as much attention.

Secondly, we can test if what we see here is similar enough to keep the user seeing information.

When we seek out information in a table format, it’s very likely that we Zoom in and filter multiple times: we’ll zoom in to check the first item, and if it isn’t the right one, we’ll go back and zoom in to the next item.

If this is the wrong item, but the information is in a format similar to what they’re looking for, they might continue looking at additional items.

Lastly, this tests whether the right design elements are grouped (E.g., the Gestalt principle of Proximity). There may be additional critical details, but they’re not grouped in this section when we Zoom & Filter.

Questions to ask at this stage:

Were the points of focus what you wanted to highlight?

Does the “Zoomed In view” provide all the relevant details?

Is the format of this view similar to what the user might look for?

Are we missing any crucial details?

Etc.

After this, we can move to the last stage: Details on Demand.

Details on Demand: Where do users find more information?

Lastly, when looking at Details on Demand, we examine the information in depth to find additional context and interactions.

Before we get to this stage, we might need to reconsider some of our design decisions. For example, we wanted them to focus on the cards, but this test shows that the icons are drawing too much attention.

Here, we consider additional things, like additional Gestalt principles. How do users know what additional items should be associated with our current focus?

In addition, where should users look for more information if it’s not readily available? We haven’t even talked about the “+” button until now. Will it provide additional details? Will it add something to the right? It might not be clear.

Lastly, are there additional relevant interactions the user might not see? I didn’t highlight it, but there are filters at the top (“Type, Label, and Status”) that would alter both these cards and issues.

Questions to ask at this stage:

What other details might be grouped with what we’ve focused on?

Where should users look for more information?

Are there any additional valuable interactions that the user might not be seeing?

While user testing might uncover many of these things, this quick process might help you resolve fundamental design issues before ever meeting with a user.

Information Seeking Behavior helps polish our design fundamentals

Part of the reason I began to learn these design tips is that I don’t always have easy access to users.

When you work in Healthcare UX, accessing patients or medical professionals can be hard. As a result, when I sat down in front of them, I wanted to make each minute count.

Perhaps you haven’t faced my problems, but you’ve encountered wasted user testing sessions. These sessions involve users who focus on minor problems (or just waste time) instead of helping you figure out critical issues where users need help.

This is where information-seeking behavior can help. While it’s not the perfect solution to address everything, it can help you check your design fundamentals and understand the unconscious process users take to find and figure out information.

This isn’t to replace user research but to get the most out of testing without users getting distracted. By understanding how users seek information, you can fix problems ahead of time and understand where people’s focus may be drawn.

So before you step into a room with a participant, take off your glasses and look at your design. You might be surprised by what you learn from it.

The second cohort of my Data-Informed Design course is starting soon! If you want to learn this valuable skill, consider joining the waitlist.

Kai Wong is a Senior Product Designer and Data-Informed Design Expert. His book, Data-Informed UX Design, provides 21 small changes you can make to your design process to leverage the power of data and design.