How to design for troubleshooting when the user workflow isn’t clear

How do you design when there’s no set path users follow?

“If only it was always this easy.” My manager said after listening to a presentation solving a simple problem.

In domains like B2B/SaaS or Healthcare UX, you don’t tackle straightforward problems. In many cases, you’re unsure what the user does to solve the problem since every case differs.

Whether troubleshooting a network or finding the proper treatment among hundreds of options, it can be tricky to understand how to help users troubleshoot.

To understand why, let’s consider a common troubleshooting scenario around alerts.

Alerts or user problems at scale

At first, designing alerts seems pretty straightforward. All you need to do is create a layout showing as much information as possible to clarify what the user should do next.

Except, that’s not what the real challenges are. That might be okay if you only design a single alert for a page.

But there are two significant problems with alerts that are often contradictory:

Alerts need to be immediately understood at a glance

Alerts, at scale, need to be easily prioritized (or triaged) quickly

The first point is easily explained by looking at a car (or airplane) dashboard. If there’s an alert you need to pay attention to, the user can’t spend five seconds deciphering it while driving 60 miles an hour: that would result in a crash.

So many alerts often use universal signals (like a triangle with an exclamation point) and specific colors designed to stand out to the users and make them notice it.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t work at scale. If you have 100 alerts designed with eye-catching colors and symbols, you will have users suffering from “alert fatigue.”

This is when users stop paying attention to alerts or don’t know what to do. Imagine you’re a doctor at a hospital who knows that when your pager starts beeping, there’s an emergency.

What happens if multiple people are paging you at once? What happens when you get paged every 20 minutes?

How do you figure out which alert is the top priority?

This has most often been studied in fields like Human Factors. The idea is simple: there is a ‘sweet spot’ regarding how much information (and stimulation) you give humans to ensure they can handle it. Too much or too little, and you run into many issues.

So, the most important thing users will do to stay in the sweet spot is triage (or priority). If you’re getting an alert, do you need to drop everything and run somewhere?

Or is this the same ‘warning’ that happens every other week on Mondays for some reason?

Their workflow, therefore, might look like this:

Get an alert of some kind

Quickly ‘glance over the information’ to get enough of an understanding

Make a judgment call: is this a top, medium, or low priority?

Take appropriate action

Designing to support this process can be done in a couple of ways.

Visual emphasis on (standardized) severity

The simplest thing to do is to use elements like color to highlight a specific severity as clearly as possible.

If “Red” means this is a critical alert and you should drop everything, that should be the only color used to alert people.

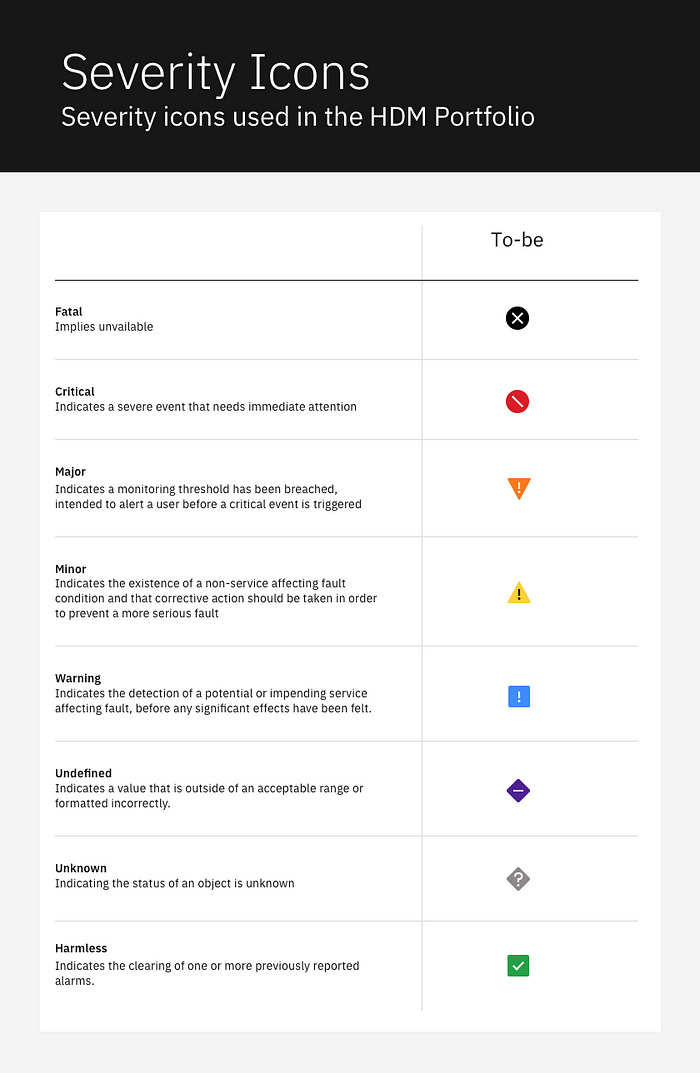

Categorize with icons

While it’s not strictly universal, there tends to be a set of icons that people pay attention to in many different ways. Oftentimes, using these icons can act as shorthand for different levels of severity.

But now that we’ve discussed designing for glanceability, how exactly can we support troubleshooting?

Troubleshooting or providing as much context as possible

While this is often where many designers talk about the power of ‘understandable error messages’, I will push back a little.

In an ideal world, errors should be made in plain language, and what went wrong should be clearly explained. Rather than saying, “error 0x0002844”, it’s better to say, “Your network adapter stopped responding.”

The problem, as I’ve learned from Engineers, is sometimes you cannot provide that information. For example, consider the “Check Engine” light on a car dashboard.

It could be that your engine is about to blow up (and cost you $5,000), or it could be that the “Check Engine light” sensor is faulty (costing you $5). The problem is that the car (i.e., the system) cannot tell you this.

You’d have to go to a mechanic or know enough about cars to figure it out. Why? Because you’re often lacking enough context to troubleshoot. You’d need to open the hood (or look underneath the car) to learn more about it.

What’s more, many of these alerts aren’t sophisticated. If we think about the “Low fuel” indicator on a car, it’s a binary switch: once the gas goes below a certain point, the alert flips on. Many alerts are designed similarly.

So, rather than hoping to design the ideal error message that lays out the problem, providing as much context as possible is more important.

For example, imagine your computer had a spike in CPU usage, which triggered an alert. It won’t self-diagnose, and it probably can’t because there’s no clear solution. The computer didn’t crash or lose data. It just ran slowly for a while.

What matters most is giving enough context about the issue to help guide explanations. This might include:

Timestamps (This happened between 1:00 and 1:15 AM Thursday)

Devices affected (This happened to Server-12)

Contact points (i.e. who do I call if this is a problem?)

Location (i.e. Where do I go if I need to fix this?)

etc.

Learning to design to provide the user with enough context while alerting will often involve space limitations.

All there is after this step is one last thing.

Link to the most likely next step

Depending on how they categorize the information, users may take several different workflows. It’s unlikely that you can cover every workflow in a single design.

However, you can link to the most likely next step. This involves understanding the user and how they work to the point where you provide the options they will most likely want from this.

In our example, one of the first things our user will most likely check is, “What does high CPU utilization really mean?” Does it mean there was a single spike of activity for 10 seconds, or was it sustained over 15 minutes?

Therefore, the most likely place they will want to learn more about is a visual representation of what happened (i.e., a chart).

By pointing them to this next likely step and seeing the visual representation, they might figure out what’s going on: “this is when our company backs up the servers, so this really isn’t an issue.”

This is how you design to support troubleshooting, an uncertain and often vague process.

Designing for branching paths is about providing enough context

Design is often much easier when there is a set user workflow.

When you’re confident users will move from one screen to the next (like a checkout process), creating the ideal path is more manageable.

However, designing for troubleshooting is often about letting expert users find the right path, which may sometimes be unclear.

To address this, you cannot always provide a structured path that 100% of your users will go through. You need to provide context and guidance at every step so that they can use their knowledge to find what they truly need.

However, doing this will help users find what they need to do, and it’s often the basis for B2B UX.

So, if the user’s workflow is not always clear or variable, learn to design for ambiguity. Oftentimes, that’s all that you need to do.

Kai Wong is a Senior Product Designer and Data and Design newsletter writer. He teaches a course, Data-Informed Design, using data to communicate more effectively and get buy-in for your design recommendations.