How to avoid accidentally giving up creative control of your designs

Why learning to mitigate shadow planning matters in the age of AI

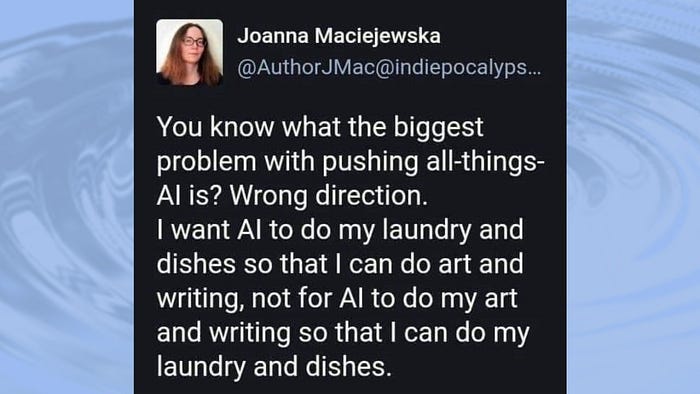

"I often fear Data might overshadow creativity, leading to safe, uninspired designs." A student in my Data-informed Design class told me, which isn't uncommon.

For those designers lucky enough not to worry about unemployment, losing creative control is often their next biggest fear.

Between organizations taking parts of the design process away and AI tools generating designs, giving up the creative parts of the design process to do menial tasks is a growing fear.

But it's not a new fear. Instead, it has existed for decades under a different name: shadow planning.

Like Amazon, but…

Shadow planning often stems innocently enough from one problem: we lack a point of reference when we start.

Product Managers might struggle to describe the new project, and you, as the designer, may be trying to understand what you need to design.

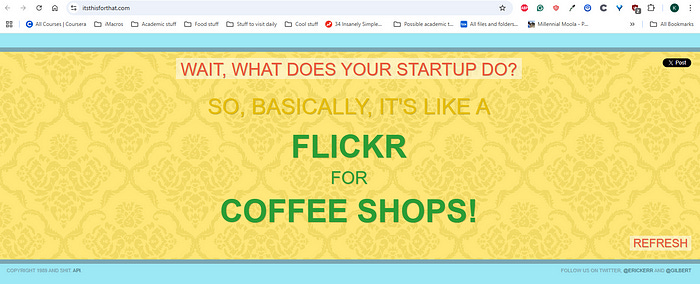

So, people reach for reference images or easy analogies. For example, our site is "like Amazon, but for pet accessories."

Whether you describe something as "It's like Uber, but for cats " or take a photo of "Amazon.com" and stick it on a mood board, this is an easy reference point.

The problem is that this can then become the basis for your design. Shadow planning happens when you imitate other websites instead of generating design ideas.

It's not always about actively imitating others. Sometimes, the Product Manager sees a reference and refuses alternative designs because "the Amazon.com version of our site is good enough."

However, imitating a website with minor changes is problematic for two reasons. The first is the fear of "standardizing designs": if 95 out of 100 websites like yours look like Amazon.com, AI will recommend websites that look like that, and it will be a "best practice" to use that single template.

That fear is known as the McDonaldization effect, which can easily affect UX. The idea is simple: you know what you'll get from McDonalds, even in a foreign country. You'll get a mediocre burger, served by people in bright uniforms, at a slightly high price.

If you didn't get into design to make degraded copies of whatever exists (with minor tweaks for logos), this is reason #1 to avoid shadow planning.

Secondly, though, the design context differs from product to product. Amazon got started selling books to customers, and now they sell a wide variety of products.

Is the design that works best for general products the same one that works well for pet owners? Of course not. There is additional context to consider, like:

Do products need to include references for scale (is a 2 ft toy too big or too small for a golden retriever)?

Is the return policy the same as Amazon's (with items covered in pet hair and saliva)?

Are we forming "pet owner" profiles or "pet' profiles?

Are there filters for certain animals (i.e., bird toys, dog toys, etc.)?

When considering that the context may be completely different, shadow planning (i.e., giving too much weight to copying others) is a surefire way to fail.

So what should you do instead? Start with the value proposition.

The value proposition, or how to avoid shadow planning

Last week, I talked about creative briefs, high-level summaries of what you're doing as a designer. These are often critical to establishing context, and it's essential to avoid 'shadow planning.'

However, a slide deck of different ideas may still be too long to convey what we're designing at a glance.

"It's like Amazon, but for pet accessories." is a short sentence that immediately conveys the general idea but can easily lead to too much imitation.

For example, when designers hear that, they might start using Amazon's grid layout, adding unnecessary features like "Subscribe and Save" buttons (depending on the context), or mirroring what already exists.

We need to create a short sentence that conveys value but doesn't rely on references to existing designs. To do this, we can rely on a process laid out in UX Strategy by Jaime Levy to create a value proposition:

Step 1: Define your primary customer segment.

Step 2: Identify your customer segment's (most significant) problem.

Step 3: Create provisional personas based on your assumptions.

Step 4: Conduct customer discovery to validate or invalidate your provisional persona and problem statement.

Step 5: Reassess your initial value proposition based on what you have learned!

Here's how this can work.

Identify your customer segment and their most significant problems

Many designers create personas based on customer segments but may not dig deep enough to focus solely on their significant problems. To start, we need to think deeply about who they are and the problems they might pay someone to resolve.

For example, 'pet owner' is a broad term. Will a person with 16 dogs on a farm have the same needs as an apartment dweller with a single cat?

In our example, let's say we narrow it down to a "surburbanite with 2–3 dogs that lives 25 minutes (by car) from a pet store."

I won't dive too deep into creating personas, as what's often more important is identifying the most significant problems these users face (and if they're willing to pay to fix them).

For example, the big problem might be, "I need a way to shop other than taking my pets to the pet store." Why?

The pets (I.e. the user has multiple pets) get too excited and want to run up and down multiple aisles

Meeting other owners with pets can be chaotic (with their pets barking at each other)

Some pets are difficult to transport (Am I taking a bird to the pet store? What if it gets out?).

Checkout is stressful (imagine how well some pets queue in line)

The alternative (leaving pets in the car in the hot sun) is also stressful

If I buy stuff without them, they might hate it, and I can't return it

By identifying who we think our user is and their most significant problems, we can begin to see if our assumptions are valid.

Create personas based on assumptions and validate them

So now, we might have a statement like "HappyPets.com is for suburban pet owners who find going to the store stressful and want to shop in the comfort of their own home."

You need to validate that statement next. Many UX professionals know how to find people similar to your user profile and talk with them.

However, your questions may be slightly different from those you typically ask. Why? Because you're trying to determine whether your value proposition is valuable.

In our example, let's say we're trying to find "suburbanite pet owners with 2–4 pets who recently bought something at a pet store." There also might be additional limiting criteria based on their assumptions, such as:

They have a car big enough to transport the pets (if they have tried to take the pets there)

They have easily transportable pets (i.e., no bringing snakes into a pet store)

They are somewhat tech-literate

etc.

The idea is to ask questions about that experience and what they did, and then finally conclude the interview with a question like this:

If there was a website, like (whatever pet store they went to), that allowed you to purchase what you needed for pets without leaving home, what would you think?

The idea is to assess whether they think your offering is valuable in an open-ended question.

For example, if they respond with, "Oh, I purchase most of my pet stuff on Amazon, " that might indicate that you need to differentiate your website from Amazon.

Or, they might respond, "Well, that sounds nice, but pictures aren't great for telling me how accessories fit."

However they respond, this will help to refine your value proposition statement.

Define your value proposition with your unique selling point

At the end of the process, you should be able to have a one-sentence description that spells out what your company's 'unique selling point' should be at this point rather than relying on analogies.

For example, imagine we've gone through this process and discovered that "the main problem with shopping online for pet accessories is that there is no context around the pets."

Many items, like a 'pet collar,' are shown with a blank white background, not around a pet's neck. Standard measurements, like "this is a 14-inch collar," are available, but measuring a pet's neck is incredibly difficult.

As a result, pet owners might pay for an online pet shop with similar animals (or things like pet mannequins) wearing accessories.

Therefore, we might summarize our website context as "the pet shop where you can see pet accessories, modeled by real animals."

Saying that instead of "Amazon for pet accessories" helps define our intentions without relying too heavily on current reality.

The loss of creative control, or why Designers fear Data

When I talk to people about Data-Informed Design, one of the biggest fears I hear in response is “Data sucking all the fun out of design."

Designers are some of the most creative people I know, but many would rather quit when they envision making minor changes to AI-generated templates.

While predicting the future is difficult, we can use past solutions to problems like shadow planning to understand how to fix this.

Rather than creating an analogy or picture that results in us imitating other companies, we can spend more time defining why your product is valuable to users.

So, to avoid poorly imitating other designs due to an innocent mistake, consider defining your project based on value propositions.

I’m having an early bird sale for The Influential Designer cohort! Sign up this week and you’ll get $50 off.

Kai Wong is a Senior Product Designer and Data and Design newsletter writer. He teaches a course, The Influential Designer, using data to communicate more effectively and get buy-in for your design recommendations.