How collecting metadata can yield better research insights

How tagging your data results in an organized and insightful dataset

Learning to use metadata has made my research analysis process much more organized, insightful, and easier to do. It’s a small extra step you can do during user testing that can impact organizing and categorizing your research spreadsheets. In addition, it can allow you to view your data in alternative views to tease out insights.

And to explain what metadata is, let’s first talk about wine.

Understanding metadata and tagging

Is it possible to tell if you’d like or hate a wine just by looking at it? Or, without drinking it, is it possible to tell if it’s turned to vinegar? The answer to both of these questions is yes, through the use of metadata.

Wine bottles themselves don’t offer many answers: the glass is usually somewhat opaque, and you can’t get many clues about how it might taste or look.

Source: Matteobragaglio on Flickr

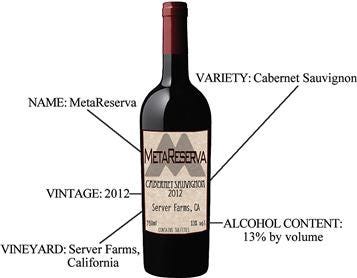

That’s why it comes with a wine label that can tell you everything that you need to know, including:

Year

Type of Wine

Where it’s from.

This data allows us to categorize the otherwise unknown wine and helps us make decisions: if we despise white wines, then seeing that on the label will help us avoid that particular wine.

https://learning.oreilly.com/library/view/data-insights/9780123877932/

Metadata, in other words, is “Data about data”: it helps us categorize, organize, and make decisions on the data that you’ve acquired, and it’s one of those things that you never really think about until it’s missing.

Tags, in particular, are one of the most useful (and quickest to implement) sources of metadata that offers you something special to your user research data: an alternative (and more valuable) view.

Understanding the broader picture with tags

When we typically think about user research spreadsheets, we think about how computers normally spit out these spreadsheets: column by column of questions and responses. It’s essential to have things in this fashion to allow you to see all of your participant’s responses to a question. You don’t want to lose their responses to Question 3 on a survey, for example. But what we want to convey to stakeholders may go beyond individual questions. For example, imagine that we want to talk about the user’s pain points: we may know that they didn’t respond too favorably to task 3, based on that column’s responses. But where else did they struggle?

Do we have to go through row by row, column by column, to try and piece that together across multiple questions?

What if we could add the “frustration” tag to specific notes instead whenever they encounter an issue?

Then, if we wanted to see where they were frustrated, we could select that tag and see all instances of that across questions, tasks, and participants?

https://uxmastery.com/how-kasasa-used-reframer-to-rebuild-prove-value-and-inspire-ux-maturity/reframer-theme-builder/

That’s what tagging offers you. It will not disrupt the way you organize your notes but instead, provide you with an alternative view to examine the dataset.

Tags are most often used to identify:

A participant’s feelings about the experience (sentiment),

What the observation refers to(for example, task, screen, workflow, question)

Specific devices or page elements for your product (content, navigation, pricing, mobile, email).

https://blog.optimalworkshop.com/tagging-your-way-to-success-how-to-make-sense-of-your-qualitative-research/

So here’s how to implement tagging into your notetaking process.

Understanding the requirements for tagging

There are two significant questions that you need to think about before utilizing tags with your notetaking process:

First, is this a user interview or usability test?

Second, what computer-based notetaking applications do you have access to?

The first question is often muddled because sometimes you are doing both: you may test a few scenarios with your users and then have a user interview right afterward if you have time. However, this is important for one key reason: you can establish tags ahead of time for a usability test, but you must wait until after a user interview to create tags.

The reason for this is simple: you don’t want to introduce bias to the user interview. You may be tempted to ask questions that lead towards one tag or another if you’ve created them ahead of time, which kind of defeats the purpose of doing user research in the first place.

The second question is equally important, but its’ significance won’t be seen until the analysis phase. Of course, you can tag your notes with pen and paper during the user test, but doing a whole lot of manual legwork afterward to count up each tag and organize these responses defeats the purpose of quickly establishing this alternative view.

There tend to be three main notetaking applications that can use tags: OptimalWorkshop’s Reframer, Evernote, and Notion. Reframer is a tool specifically meant for UX Research, so the User Interface is catered towards quick and efficient tag use, but it’s also pricey (with a free trial). The other two notetaking applications require a little bit more setup, but they’re often free and widely available. Whichever the case, once you answer these two questions, we’re on to the next section.

Creating tags

As I said before, you should do this process after a user interview to avoid bias, but regardless, you’ll eventually need to come up with a list of tags. Which ones you use may depend on your research questions, but here are a few categories of tags you might want to include.

Sentiment tags:

Positive

Negative

Painpoint

Confusion

Frustration

Concern

Problematic

Etc.

I’ve talked about sentiment tags previously, but they’re essentially a quick way to summarize your user’s overall feelings about the experience.

The sentiments you can capture can range from simple to more detailed, depending on what you want to capture. For example, a simple positive/negative tag system allows you to capture what works and doesn’t work for users, but you likely want to extend this out further to point out specific problems.

Painpoint identifies a specific usability issue, and it’s usually found when talking about why something doesn’t work. However, sometimes you want to dig further into the specifics of why this is a painpoint. The next couple of tags help to refine this.

Confusion usually occurs when navigation or Information Architecture issues, such as clicking on the wrong menu item. If people run into problems and are unsure how to proceed, that is confusion.

Frustration tends to be a tag that occurs when what the user expected to happen doesn’t, or if there are problems with the interface that require additional work. For example, if users think they know how to proceed but it’s not working, that’s frustration.

Concern is a tag typically based on errors (or potential slips) that the user could make and more significant issues. For example, some users might express concern regarding the ability for users to delete all options without a secondary confirmation question.

Last of all, problematic tends to be a tag that comes up when your design is not quite right: for example if you’re using radio buttons, but that’s not the right design decision for this use case, many users may express this as problematic.

However, these are not all of the tags to consider.

User tags:

Want

Need

Suggestion

Quote

These tags are often valuable for keeping track of what users say if you want to call attention to them later. For example, tracking insightful quotes or things users explicitly stated (needs/wants/suggestions) can help track them later.

Workflow tags:

Expectation

Approach

*Variation

These tags keep track of how the user’s workflow may differ from the official policy or workflow. For example, expectation refers to what the user expects when actions are taken (i.e., when you click “Next”), and Approach refers to what they do currently in terms of next steps.

You may want to exclude the “Variation” tag if you’re showing these tags publicly, as you do not want to advertise certain users do something different than official policy. However, “Variation” can be an important way to track when the user’s workflow differs from official policy or workflow.

Once these tags are established, then it’s time to talk with your notetakers.

Talking with your notetakers

The number one thing that you need to get across to your notetakers is that no matter what, notes come first before any tagging. Tagging your notes can occur afterward with no problem, but we can do nothing if you don’t have any notes.

Remember, metadata is “data about data”: if you don’t have any data, you can’t create any metadata about it.

However, assuming that they’re focused on notetaking first, they may tag some of the notes in real-time. Some tags, like “Quote, Suggestion, and Frustration,” can easily be added to the notes without much issue.

But the other thing you have to do is make sure everyone has a clear understanding of what each of these tags means and when you should use it. For example, mixing up “Confusion” and “Concern” may throw your initial analysis for a loop, but it’s not the end of the world if this happens because of the next step.

Revise and analyze

Because these tags may be coming from different notetakers (and you might not have had a chance to read over the notes yourself), you should take time after the interview or test to read over the existing notes and tags and figure out if they’re valid.

This may sound like a lot of effort, but in reality, it’s just adding a step to your research findings analysis.

In fact, if you’ve kept up with tagging, this process might be a whole lot simpler due to a few reasons:

Your notetakers might have been able to capture a lot of good tags during the notetaking sessions

During the debrief, different notetakers reviewed their findings and made some progress in addressing things

Your notetakers (and yourself) can reach a consensus regarding tags much more manageable for later participants.

Doing this allows you to quickly review and check your tags to provide clarity and insights for your data analysis.

Adapting metadata for your data analysis

Sometimes, the least favorite part of the user research is staring at a big spreadsheet and trying to make sense of your results. This can be compounded by the fact that sometimes, you weren’t even present for some of these user interviews (if you’re part of a larger team). Keeping track of the metadata throughout this process might be a small extra step, but it can help analyze and make sense of data in a larger picture.

SO if you’ve ever found yourself tracking your user insights across an entire study, consider using tagging. It’s simple metadata that can nevertheless offer a ton of insight.

Kai Wong is a UX Specialist, Author, and Data Visualization advocate. His latest book, Data Persuasion, talks about learning Data Visualization from a Designer’s perspective and how UX can benefit Data Visualization.