Design as a craft will not die out because of new technologies

Designers are craftspeople who can create our best work on napkins

Photo by Abhishek Saini: https://www.pexels.com/photo/person-molding-a-clay-pot-3145866/

There’s an question that I’ve heard recently that’s bugged me: "Aren't you bored of UX Design?”

She brought this up because, in her opinion, UX Design was boring because no matter your methods, the outcome is always the same. You solve whatever problem the business hands you and then hand it off to developers. Even if you have good ideas about what the business should be doing, it’s outside the “scope of a UX Designer.”

While I agree that Product Design is a natural extension and a better fit than UX Design nowadays, this is missing the point of our craft. UX, at its core, is the profession of craftspeople, which many of us might have forgotten about.

In the face of many forces (like AI and standardized design systems) that make us worry about the future of UX, it’s good to revisit the core of our craft and understand why it’s still helpful (and how you can still have a job).

And it starts with an age-old argument around McDonaldization.

The McDonaldization of UX and why craftsmanship matters

McDonaldization is a concept by George Ritzer about five principles related to production and work that mirrors fast-food chains.

Efficiency — streamlining and optimizing processes to provide maximum operative efficiency in completing objectives.

Calculability — quantifiable delivery of a product trumps quality. A high amount of a mediocre product is superior to a low amount of a quality product.

Standardization — consistently providing the same quality product (like a McDonald's cheeseburger).

Social Control — standardized employees (uniform behavior and interactions).

The irrationality of Rationality — rational systems become irrational when they subvert and dehumanize employees.

The idea is that even if you’re in a foreign country and can’t read the language, you can go to a McDonald’s and get the same experience: a mediocre cheeseburger served quickly by a person in uniform with minimal conversation.

UX, for a while, has seemed like it would adopt many of these practices and turn designers into a ‘plugin’ for business. With standardized design systems, static processes that designers must always follow, and workshops where “Everyone is a designer,” it seemed it was inevitable that we’d turn into “template flippers” instead of “burger flippers.”

That’s not even accounting for throwing things like Data into the mix.

However, in the face of all this standardization, what’s shined through are the things that make UX unique: the skills that make us craftspeople. In essence, there are three parts to this skillset:

Listening and clarifying ideas from users, business owners, and others

Visualizing and iterating on those ideas through mockups and prototypes

Communicating a polished final prototype (and intentions) to your team

These three skills are the core of our craft, and understanding them is more important than ever.

Understanding intent, or why craftspeople still exist in the post-industrial age

Ask yourself, why are there still craftspeople that exist in a post-industrial age?

In the age of mass-produced IKEA furniture and factories that churn out standardized dishware, why are there still furniture makers and glassmakers? The answer is simple: there is still a demand for it. And often, the demand comes from having someone there who can interpret what a person wants from what they’re saying.

Some of you might have encountered this need before, likely from people misinterpreting words. For example, a Product Manager uses an analogy to describe what they’re talking about (“put something like a list of names here”), and then Engineers take that literally and put a list of names there.

This is why UX matters. Instead of taking things at face value, we dig and ask questions, clarify ideas, and challenge them to explain them better to get to what they want: the underlying need or explanation that might not be clear.

Craftspeople do the same thing: they listen to the customer describe their ideas, help them clarify what they’re looking for, and then have some idea of what to produce.

However, doing this allows us to take the next step, which distinguishes us as Designers (and makes us craftspeople): visualizing through creation.

Visualization is one of our significant (and often) forgotten superpower.

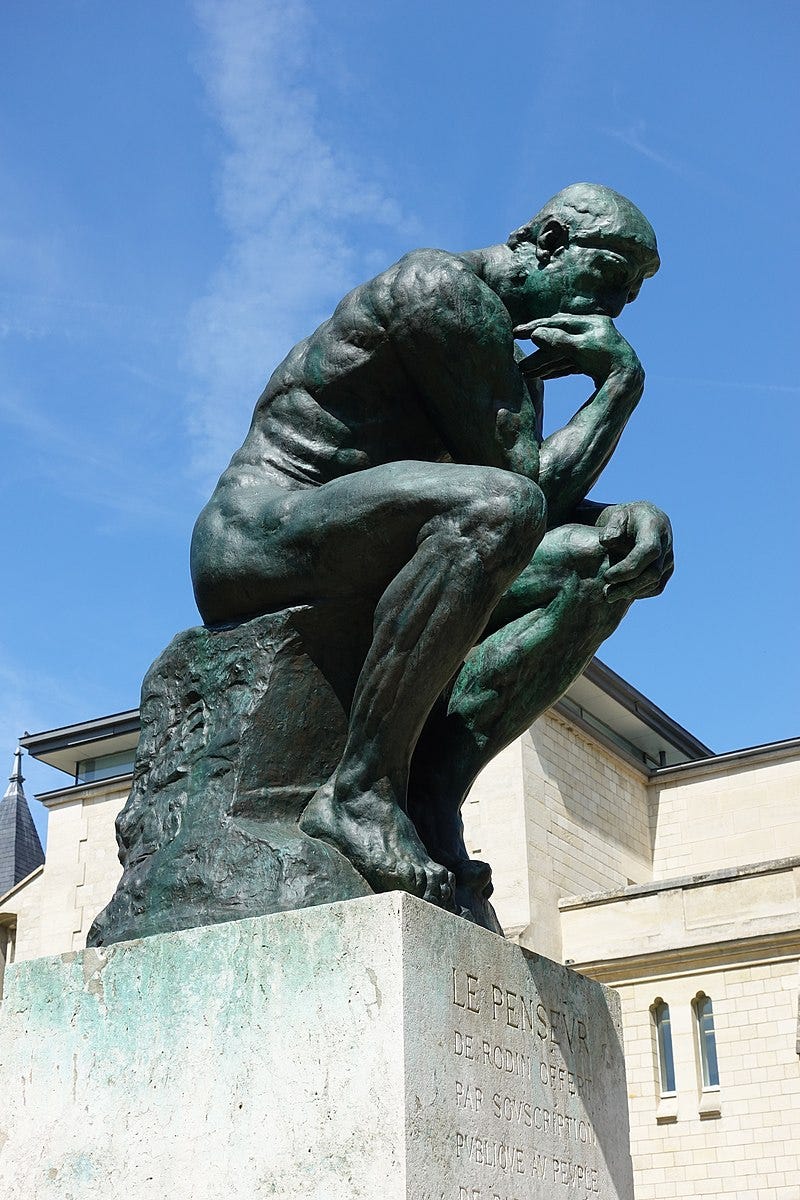

“I choose a block of marble and chop off whatever I don’t need.” -Auguste Rodin

Everyone can visualize figures or animals in their heads. However, few people were as good as Rodin at chipping away pieces of marble to reveal sculptures of figures and animals.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Thinker#/media/File:Mus%C3%A9e_Rodin_1.jpg

This makes him a master sculptor, and it’s the same skill that we as designers often use (and forget about): visualizing ideas.

Everyone on our team can probably imagine what the final product might look like, but few can visualize it in sketches in a way that suits both business and user needs.

(Image)

The ability for designers to hear an idea and turn it into a visual that can be shared, refined, and critiqued is a primary design skill that businesses often seek from UX. This ability is also a skill that can’t be McDonaldized, no matter how advanced AI becomes.

However, one of our advantages nowadays is that the product isn’t (literally) carved in stone. Instead, it can grow and iterate over time through constant feedback from all sides. Theoretically, as long as designers practice these two skills, we can craft the perfect product that fits everyone’s needs.

Yet the frustration around being a UX designer doesn’t usually come from these two aspects: it tends to come later, with the handoff. With that comes the last aspect of being a design craftsperson: handing off ideas and expressing your intent.

Communicating your design ideas through handoff

The statement about UX Design being bland probably isn’t about boredom: it’s frustration. If you created a perfect design for your users, it could still become a crappy product if your Product (or Engineering) team decided to go against it.

I’ve experienced that more than a few times. Once, I was even told, “Don’t go look at the final product. You’ll be upset at what it turned into.” I’ve even met Product Managers from UX because they were tired of their designs being butchered.

However, here’s the harsh truth: unless you’re the CEO of a company, you’ll probably face this in whatever job you take. For example, Engineering might be unable to do what they want because of budget constraints. Likewise, Product Managers might have ideas cut due to technical constraints.

That’s not even mentioning that an executive might come by and throw out your ideas in favor of something else.

However, you have to ask yourself: does that possibly matter to your skill as a craftsperson? After all, if you work for a job that constantly undercuts the design that you create, you can look for another job.

What companies will be looking for from you are not necessarily the failures of a final product due to executive meddling: it’s the skill you have in following that process to your completion point and delivering what is necessary.

Learning to roll with the punches and iterate based on other people's feedback is often not as painful as handing off your work and seeing someone else wholly destroy it. However, as designers, what’s important to know is not that we get to build the final product: what prototypes and other things are about is one thing in particular—ensuring that our ideas and solution get across to our team visually, as best as they can.

If things get lost in translation, or if Engineers interpret your design (rather than following it directly), you can learn to augment those skills or documentation to avoid those situations in the future. But Designers always hand over your work, which means we won’t be the ones to build the product (and have the final say).

But that doesn’t mean there’s no value in the craft or art: some of the greatest artists have practiced similar skills.

Design is a craft that can take place on napkins.

Pablo Picasso, the world-famous painter, was once drinking at a restaurant and doodling on a napkin at a cafe.

Someone then approached him as he was leaving and asked for the napkin when he went to throw it away.

Picasso paused and said, “Certainly, that will be $3000.”

The woman was taken aback and said, “It took you fifteen minutes to doodle that!”

Picasso replied, “No, it took me 40 years to do that.”

UX Designers practice a craft much like Picasso: the ability to visualize something from nothing, refine it based on feedback, and hand off a ‘finalized’ prototype for someone else to build.

It’s a valuable skill pipeline, and even if the final product doesn’t always turn out how you might like, you’re always learning and creating around that core skill set.

I think augmenting your skillset with Product Design (or Data-informed UX Design) might be a smart career move, but that doesn’t mean your UX skillset becomes invalidated. On the contrary, the craft of UX will always be necessary and welcome, and polishing those skills Isn’t a waste of time: doing so not only makes him a more attractive job candidate, it improves the way you think about the world.

Want to become a UX professional? I’ve written a free e-book explaining how to make yourself an ideal UX candidate.

Kai Wong is a Senior Product Designer and a top Design Writer on Medium. His new book, Data-informed UX Design, explains small changes you can make regarding data to improve your UX Design process.