Creative briefs: the best way to track design projects if you’re short on time

How to provide “just enough context” for your projects

Designers often assume everyone has context, a mistake that results in a blank look when presenting your ideas.

Whether it’s an awkward silence after you present user research or executives interrupting and asking questions, you might have suffered from assuming your team has context.

That’s why taking a step back and giving more context is often a critical part of most presentations.

However, it often turns into a Goldilocks problem.

The most common mistake, especially in job interviews, is to provide too much context. But too little context doesn’t help you, either.

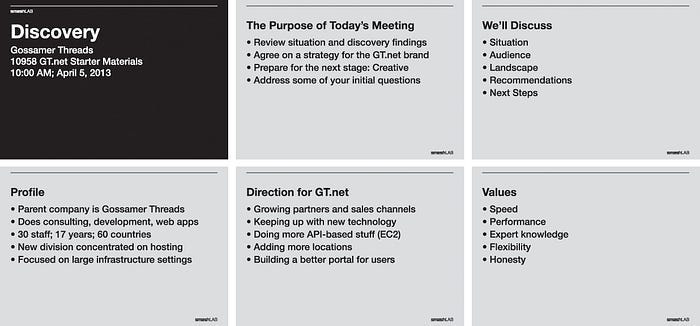

What’s the exact right amount of context to present your ideas? It often takes the form of a Creative Brief.

Creative briefs: a designer’s secret template

In The Design Method: A Philosophy and Process for Functional Visual Communication, Eric Karjaluto highlights how creative briefs are often one of the most versatile and powerful ways to provide context.

Why? Because it’s versatile enough to be helpful in several critical settings:

Getting a new person up to speed

Setting up to talk about the value of your design work and decisions

Providing context to executive stakeholders (like CEOs)

Keeping track of design decisions for your portfolio (like a design diary)

Identifying the problem you’re solving

How can one thing do all of this? By summarizing, as clearly as possible, the significant questions that caused this project to get started.

It sounds straightforward, but often, many stakeholders get caught up in the daily work of large projects.

Whether it’s working on “Sprint 6 of 13”, tackling the latest Development hurdle, or addressing whatever new thing that executives think of (i.e., “Let’s integrate AI into our process!”), many stakeholders often lose track of the high-level view.

In addition, as you iterate on your designs, it’s essential to remember the project's primary purpose, as sometimes you mind the project’s purpose morphing across iterations and struggles.

Lastly, it’s a way to list out the basics necessary for design portfolios. Why? The same high-level overview you want to establish with stakeholders is what you’ll need to provide recruiters and interviewers to get them to understand the value of your work.

So, what are the elements of a creative brief, and what do you need to express?

Provide not only design context but business needs as well

The #1 mistake designers make, which leads to portfolios that don’t have much impact, is that you need to ask about the business context.

“Because the business told me to.” Is not a good reason for designing something. We know it but often don’t ask your team enough questions to understand.

For example, I recently spoke with a junior designer designing an interface for nuclear engineers. He was about to run into one critical question that every recruiter would ask him: “So what?”

The reason why? He said, “The problem with the interface is that it’s outdated.”

Businesses don’t spend much money re-designing an old interface for no good reason. Instead, it would have likely been for a few critical reasons:

The interface is causing issues: Users are making errors or wasting a ton of time because they’re not used to the old UI, which causes business problems.

The learning curve is too steep: The system works well for experts but requires 2 weeks of intensive tutorials, workshops, and hand-holding for new users to understand it.

There’s a negative perception of the product: Users think that “because this thing is old, it must not be worth a lot.” harming the businesses’ bottom line.

This is why I like asking my team a single question to help this process:

“How are you measuring whether the project is a success or failure?”

By understanding how businesses define success and what they care about, you can help define how the business context fits into the creative brief with a single question:

What are you designing on a large scale?

For example, after asking that question, you wouldn’t just say. “I’m re-designing an old interface.”

You’d be able to say, “I’m re-designing an old interface to (make it easier for new users to learn the product/help users avoid making mistakes).”

After that, you need to focus on change.

MVP, or why must we change?

The next thing you must do is highlight the need for change. After all, most businesses follow the idiom of “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

If the MVP works perfectly fine and it’s not costing a ton of money, businesses are not incentivized to change.

So the next thing to highlight is “What is the current problem?” In essence, you want to highlight why the current experience is not ‘good enough’ from the user’s point of view.

The idea is simple:

What is the problem with the current design that led to a business paying you to re-design it?

If you’re having a hard time addressing that question, you can also try this one:

“What (desired/undesired) user behavior must we address?”

After all, design, from a business perspective, is about changing user behavior.

For example, if you’re re-designing an old UI for Nuclear Engineers because the learning curve is too high, some behavior is associated with the current process. Perhaps new users:

File a bunch of customer support tickets to help with the process

Requires supervision for 6 months to learn the process

Make tons of errors that others need to correct.

Highlighting the problems like this, in plain terms, helps show the value of design. By clarifying why the current solution doesn’t work, you also clarify the problem you’re attempting to solve.

After that, we can begin brainstorming our current solution (which will change with each iteration).

Understand How Might We, from a behavior change perspective

A bad example of this is saying, “How Might We design a table to allow for easy sorting and filtering?”

But that’s not what it’s meant for. Now that we’ve established the previous two sections, we can use “How Might We” to provide better context around the project's current state.

What you want to do instead is think about How Might We, in terms of behavior change.

If we were to think, "Our current design needs to change because Nuclear Engineers require 6 months of training to really use our interface.”

Then How Might We forces us to realize that there are issues during onboarding that need to be fixed. This might include:

“How might we get users to learn certain concepts during onboarding without getting overwhelmed?”

“How might we limit the number of choices we’re forcing our new users to make during setup?”

“How might we make it less likely to choose advanced options likely to cause critical issues?”

etc.

By defining the large-scale context and the current design problems, “How Might We” becomes a valuable tool for discussing the current design approach for fixing these problems.

This not only helps us understand the scope of behavior change that we hope our design has, but it also helps us understand and establish why it matters.

It’s more important than ever to establish Why

Nowadays, it’s not enough for Designers to talk about “What they did.”

Businesses aren’t just looking for high-quality images of designs (although it helps).

In an era where businesses must justify every dollar spent, identifying the reasons “Why” and spelling it out in plain language help show that Design isn’t just visuals. It’s something that identifies problems and shows value in solving them.

There’s no better time to think about it than when you’re working on a specific project.

That’s why the creative brief can be so important. Rather than a daily tracker or guessing 6 months after the fact, the creative brief is a versatile overview that can be plugged into a dozen places.

So, if you’re wondering how to summarize your work, try leaning into briefs.

Kai Wong is a Senior Product Designer and Data and Design newsletter writer. He teaches a course, Data-Informed Design, using data to communicate more effectively and get buy-in for your design recommendations.

This was interesting Christopher, I'd like that you covered it with practical example